DIOs – Decentralized Impact Organizations for the Climate

By Olliten for ”Seeking a New Kind of Public Good”.If you want to get involved in more discussions like these, join the Public Library. We are running out of time. Every region of the world is seeing irreversible damage due to climate change. The new report by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate (IPCC) states that “unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C…

By Olliten for ”Seeking a New Kind of Public Good”.

If you want to get involved in more discussions like these, join the Public Library.

We are running out of time.

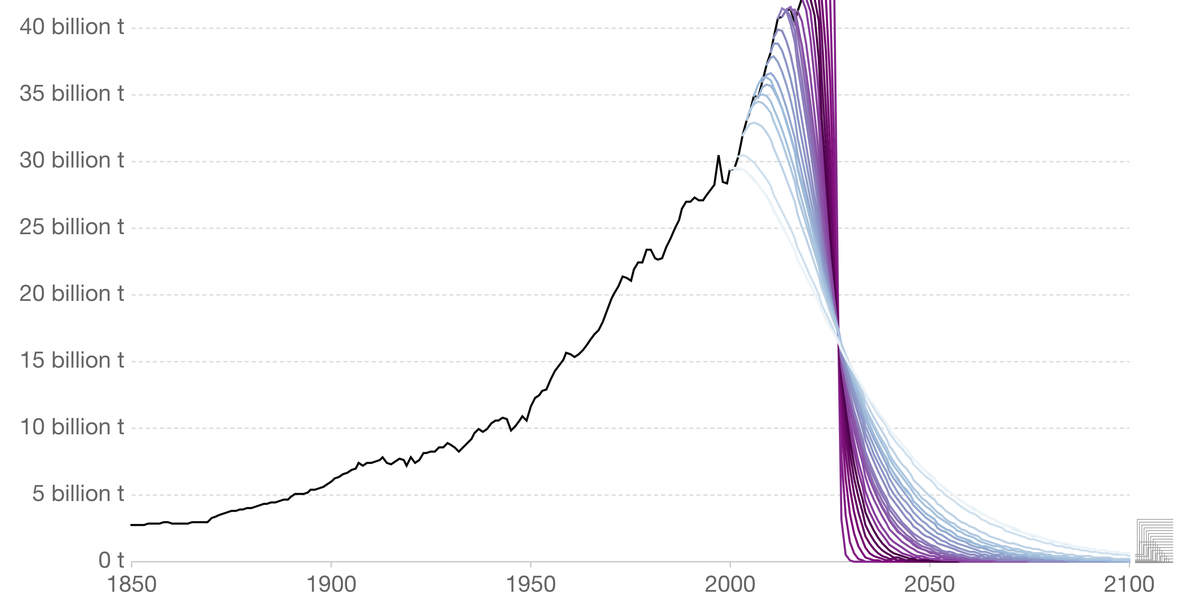

Every region of the world is seeing irreversible damage due to climate change. The new report by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate (IPCC) states that “unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach.”

In other words, extreme mitigation is needed.

The challenge is daunting. Getting gradually to net-zero emissions is not nearly enough — we also need to draw carbon from the atmosphere.

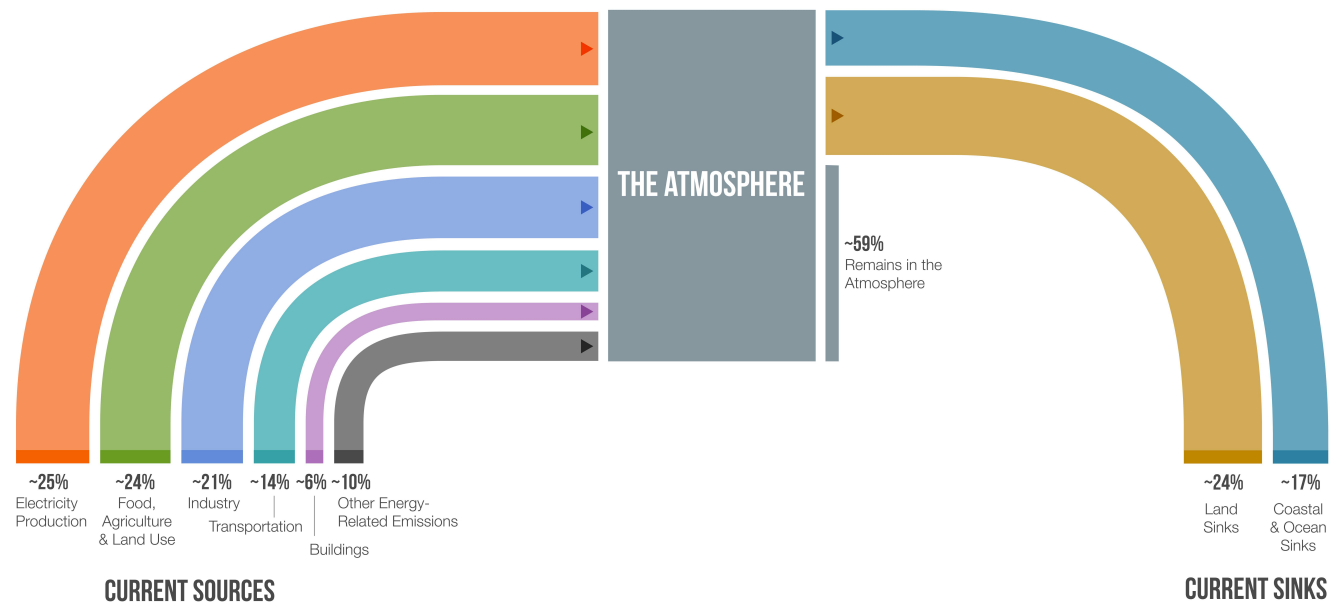

Almost every part of the economy needs to be transformed — from eliminating emissions in electricity production, food, agriculture, land use, industry, transportation, and buildings to creating natural and artificial carbon sinks on land and in the oceans.

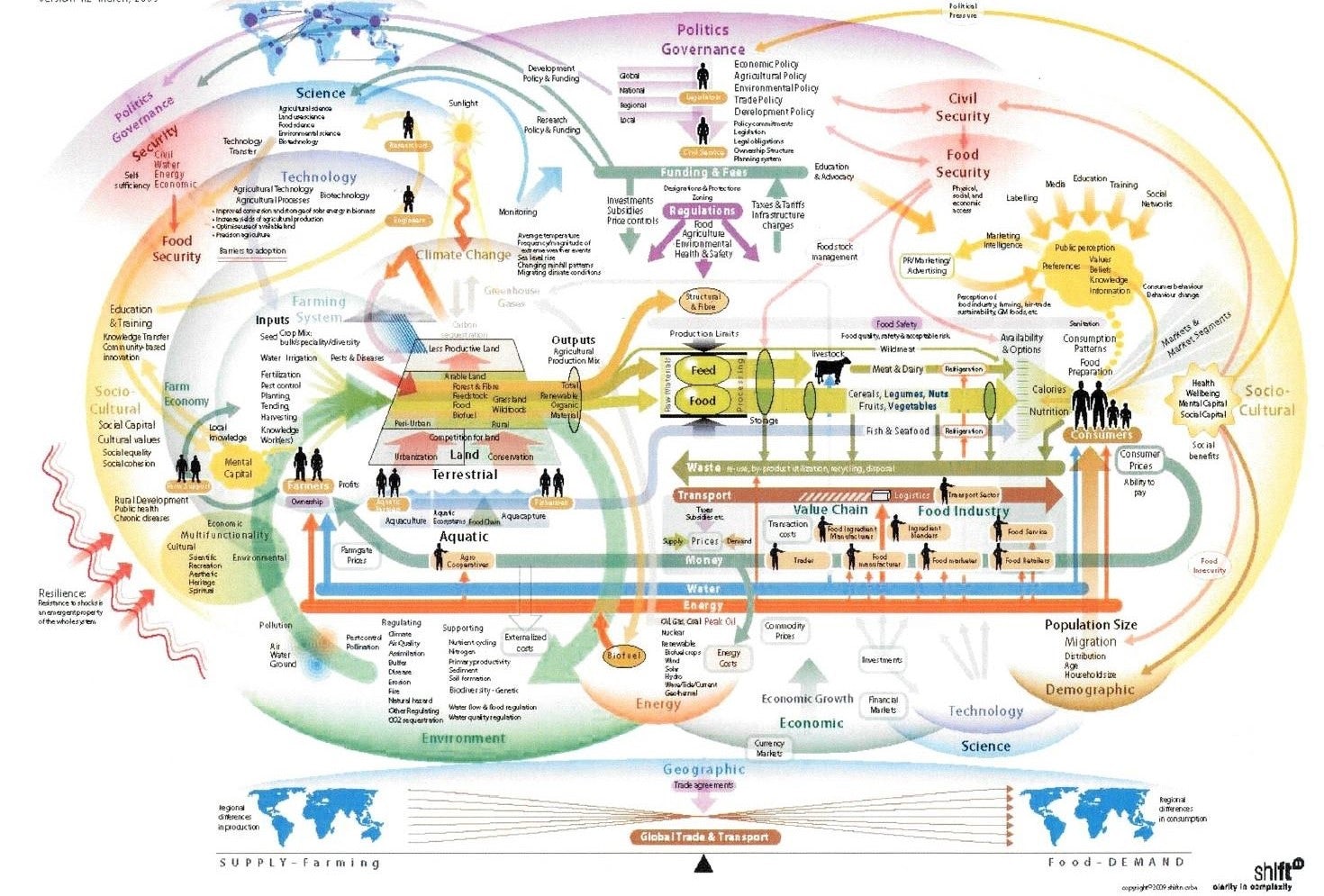

The undertaking requires integrated interventions in economic, political, technological, and social systems along whole value chains. All levers of change must be simultaneously engaged: technological innovation, policy and regulatory frameworks, financing models, social norms and behaviors, skills and capabilities, citizen participation models, identities and narratives of individuals and collectives, business models, and production and consumption paradigms.

Furthermore, fixed plans are bound to fail because the systems are complex and behave unpredictably (see Picture 3). Instead, we need to experiment our way forward.

The problem is that the current market pull is not sufficient enough to incentivize large-scale experimentation. Yet, coordinating these experiments across different systems and levers over the next decades is impossible for centralized actors such as governments.

Therefore, we need to create new market mechanisms that reframe people’s thinking to the longer term and better subjects for their attention.

Social Policy Bonds as Market Makers for Public Goods

Enter social policy bonds.

Social policy bonds (SPBs), initially proposed by Ronnie Horesh in 1988, are financial instruments that reward people when they achieve social goals.

The bonds are simple in design. They do not bear interest and are redeemable for a fixed sum when a specified social objective is reached. The bonds are distributed to preselected agents or auctioned off to the highest bidders. After this, they freely trade in the open market, causing their market value to rise and fall.

As an illustrative example: The city of Helsinki wants to reduce Helsinki’s annual carbon dioxide emissions by 80% by 31st of December, 2030, as measured by real-time data from NASA’s carbon-sensing satellites. The city agrees to pay out $60 M in total when the reduction is achieved. It issues 600 000 carbon bonds redeemable for $100 at the date of reaching the target and then auctions those off to the highest bidders among its ~ 600 000 citizens, who can later sell the bonds or buy more on secondary markets.

Despite their simplicity, SPBs have a rich set of properties that make them excellent tools for climate finance:

- They create a group of bondholders incited to efficiently achieve the targeted social objective or pay others to do so. Furthermore, the bondholders are incentivized to share ideas, skills, and resources that help reach the objective.

- The market mechanism will ensure that the bonds end up in the hands of bondholders that can most efficiently create a meaningful change in the KPI to which the social objective is tied. Inefficient bondholders reduce the likelihood of reaching the objective and thus lower the price of their tokens. At some point, the inefficient bondholders will benefit more from selling their bonds to efficient bondholders than holding the bonds themselves. In addition, the bonds are solution-agnostic and thus able to engage any lever of change necessary.

- Some bondholders may contribute to only a few of the early processes necessary to achieve the objective. Once these investors have contributed and seen the value of their bonds rise in line with the increased probability of the bonds’ redemption, they may sell the bonds to the next bondholders with more expertise in carrying out the later processes.

- The market for the bonds provides valuable information for both investors and bond issuers. The higher the price relative to the payout, the faster or cheaper will the specified goal be achieved. This information will, in turn, help decide where to allocate society’s scarce resources.

Yet, for all their attractive properties, social policy bonds have never been put into practice after their invention 33 years ago. There is no research (that we know of) on why governments have been reluctant to try them out. However, we can speculate why, by comparing Social Policy Bonds (SPBs) with their more famous cousins Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) that since 2010 have been issued 214 times in 35 countries.

SIBs are like SPB’s except that they are non-tradeable. This difference may sound tiny, but it radically changes the way goals are pursued: Because SIBs won’t change hands once issued, governments need to carefully pick and choose the delivery partners and the theory of change against which to measure impact. Thus SIBs are suited for short-term goals, where the solution can be imagined in advance.

On the other hand, social policy bonds work best for ambitious long-term goals that require diverse, adaptive, collaborative, and often uncertain approaches. These features may make SPBs challenging for governments to issue: long timelines could exceed budgetary periods, ambitiousness might surpass branch responsibilities, and relinquishing control over how public goods are delivered could conflict with the cultural premises of governments and their industrial, linear, and redlined past.

It is thus unlikely that governmental institutions will spearhead social policy bonds. Yet, for SPBs to make a real difference, we need their financial support.

How to get them on board?

Decentralized Impact Organizations (“DIOs”) to Supercharge Social Policy Bonds

Crypto has transformed grassroots-level organizing. For the first time in history, it is possible to economically align networks of strangers into working together by using programmable incentives and providing them with tools to make decisions and govern shared resources in a decentralized manner. These new organisms are called by many “DAOs,” Decentralized Autonomous Organizations.

An SPB and its bondholders together form an entity very similar to a DAO: the bondholders form a grassroots organization and share an economic fate via the bonds they own. What is particular about this type of “DAOs” is that its token (the bond) derives its value from the quality of a public good. To distinguish it from generic DAOs, we’ll call them “DIOs,” Decentralized Impact Organizations.

The technology for creating crypto-native DIOs already exists. Six months ago, UMA Protocol launched a new crypto-derivatives product called “Key Performance Indicator Options.” KPI options were initially created so that crypto protocols could trustlessly guarantee that their community receives rewards for hitting milestones such as increasing Total Value Locked (TVL). However, their design allows them to be used for SPBs, too.

KPI options are synthetic (ERC-20) tokens that will pay out rewards if a KPI reaches predetermined targets before the given expiry date. Every KPI option holder has an incentive to improve that KPI because then their option will be worth more.

Launching an SPB as a KPI option token is simple:

- Define a KPI metric for the synthetic.

- Determine parameters: a KPI target, an expiry date, and a payout value.

- Mint tokens by depositing collateral to be used at settlement.

- Set up a secondary market on Uniswap or other AMMs for ERC-20 tokens.

- Distribute tokens by airdropping them to preselected addresses or by selling them for stablecoins via a Gnosis Auction or by other means.

DIOs that take advantage of KPI options not only democratize the creation of SPBs. They also radically expand SPBs’ properties. With KPI options…

- Anyone can issue tokens for free in a matter of hours – skipping month-long paperwork and massive costs required to list assets on traditional secondary markets.

- Anyone can add collateral, which enables multiple parties to join a contract to incentivize the change they want to see in the world. This property is not something to overlook. Philanthropic donations to mitigate climate change are proliferating, and for example, in the U.S, between 2014 and 2019, they nearly doubled from $900 million to at least $1.6 billion. In addition, crowdfunding of climate goals may rocket in the coming years.

- Funders can add more collateral to the contract at any time before expiry. This feature is handy because the optimal payout level is hard to determine beforehand. The size of the payout does not necessarily increase the probability of success linearly. Therefore market reaction can help determine whether the initial payout is too low and needs to be improved.

- Investors owning a token can split a primary goal into several secondary goals and fund the secondary goals directly instead of picking and funding projects that may or may not succeed.

- Tokenholders can access the rapidly developing set of tools for decentralized organizations and 10X their ability to find each other, create a sense of mission and belonging, and coordinate action across geographies.

Well… at least that’s the hypothesis. What we now need is a pilot.

The next step: a DIO pilot

The purpose of this essay is to propose DIOs as a novel mechanism for climate change mitigation and expose it to scrutiny before designing a real-life pilot. To make the proposal more concrete, we next present some design constraints for the pilot and sketch an outline for a “launchpad” for DIOs.

The primary goal of the DIO pilot is to test the concept and learn whether the mechanism can produce expected results in real life.

SPBs are well suited to climate mitigation because reducing greenhouse emissions focuses on a well-defined and measurable global externality. However, a good KPI target for the pilot needs to fulfill several requirements:

- The target defines a hard problem that requires diverse, adaptive, collaborative, and uncertain approaches to solving it.

- Yet, the target can be reached within months.

- The underlying phenomenon that the KPI measures and at least one data feed for the KPI must be too costly to manipulate.

- The target can attract enough climate mitigation capital.

The secondary goal for the pilot is to validate the need for a “launchpad” for DIOs — a website that can help climate mitigation funders and operators build and scale DIOs in an instant. Potential features could include:

- Find and follow a wide variety of climate KPIs in one place

- Find preselected and vetted data feeds that can be used for issuing new tokens

- Issue, collateralize, airdrop, auction, and recollateralize tokens

- Mint NFTs in return for funding DIOs

- Find issued tokens, and buy and sell them

- Find & connect with other tokenholders and communities for each issued token

The global climate finance market must grow at an unprecedented scale of $3-5 trillion per year to meet the Paris Agreement targets. Novel market mechanisms are needed to channel those funds effectively.

The job for us now is to concretely demonstrate to parties funding climate action that decentralized technologies can provide a viable alternative.